What the job is - or, "Dealing with lemons"

"My job is not about taking pretty pictures - I wish that it were."

- so I wrote in my last article. Sure enough, the very next shoot had me being asked to get a portrait incorporating a specific background, a large, branded vehicle which could not be moved. Unfortunately, the combination of timing and the weather meant that this was (possibly) going to be impossible, or at least a pretty ugly picture. The harsh afternoon sun - such as it was and relative to the background - would be directed into the subject's eyes. At best, it would force a hard squint. At worst, it would destroy his retinas.

When I raised this small lighting issue, my client probably retorted that on nearly every job I claim the light is in the wrong place, or that there's not enough of it, or that it's just wrong, somehow. Then (I expect) they would have said something about me whingeing (but to be quite honest, I usually stop listening at this point).

Well, they were probably right. Not about the whingeing - no. But I do complain quite a bit about the light being wrong. As well as almost everything else.

The main idea is this - situations are sometimes unpredictable, the lighting often unsuitable, the location rarely ideal. You very often end up doing things that 'aren't photography' in order to adapt or change the situation. If it's something you might consider way out of your job description, it can be irritating.

However, that part of the job, as I've come to learn, IS the job.

Anyone can produce a decent picture given enough time and ideal lighting*. But the working photographer's job is to innovate, to be pliable and resourceful, adaptable. Pull things out of the hat. Foresee problems and resolve them. Change up at the last minute, and under pressure. Because the lighting is never right. And often, other things are wrong, too.

The thing to take away from this is very important, so I'll state it very clearly: loads of things appear to get in the way when shooting. I say 'appear' - but to think of them as distractions or nuisances is a *fundamental* error. I'll state it again - it's ALL part of the job. Photography might only be part of what we're doing. We're dealing with many other things first, in order to enable the photograph to be taken.

So, it's about going with the flow, thinking around the problem. Facilitating and adapting. Not getting caught up sulking - "This shouldn't be like this," or, "I was hoping for that", or, "The light is terrible". It it's a barrier, it gets in the way of the job. Therefore, dealing with this stuff IS the job.

On the other hand - happily - I would say that roughly half the time, shoots are fairly predictable, and everything's tickety-boo. The office space is the (dismal) location you expected it to be. Or, working outside, it doesn't end up tipping down with rain - despite those ominous black clouds. Or, doing portraits, you actually get to use (most of) the twenty minutes you were originally promised.

These shoots are fairly 'routine': things go roughly as hoped or expected, and the skills called upon are what I would consider central to being a photographer. These, then, are the good days. They allow you to just get on with the job, to practise, learn and improve. To expand your patter and find new ways to blag coffee, biscuits or pens. You can think about ideas, lighting, framing, illustrating the concept, telling the story, whatever. By and large, most things on these jobs are the same as the last time you did something similar somewhere else. You could even dare to go so far as to say you can actually plan these shoots**.

The other half, the ones we're talking about today, aren't so predictable - often regardless of planning. They contain these seeming obstacles, changes of schedule, extra hassles, crappy light, and apparent nuisances. And we've agreed to accept these and work through them.

Sometimes, however, there are curveballs which really stretch things. People problems spring to mind first. I've had several people at a workshop who had asked not to be photographed (not even in the background), but who then took centre stage in most of the activities. Which made photography of pretty much anything else impossible.

I've had a client who insisted their logo be in shot - despite the logo being very small, and ankle-height. They became rather incensed when I explained how it wouldn't work very well (and it didn't).

Location problems are common. We're especially at the mercy of the weather in England. I was recently caught in torrential rain for a shoot about city workers enjoying summer barbecues.

And indoors, many public buildings have horrific lighting. Offices with nasty spotlights embedded into the ceiling. Dark corridors, small windows, and useless spaces.

I had a shoot in a (sort-of) theatre, and I remember the "stage lighting" only covered half the people on stage. The other half could barely be seen by the naked eye - let alone a camera.

Light, people and location issues are general and universal. I suppose the thing with it is that there are other curveballs and hazards peculiar to certain types of job. At conferences, for example, there's always that one speaker who never looks up. Which results in shots of a depressed person at a lectern talking to his navel.

At jobs where props are required, sod's law says they'll forget to bring them. I shot a pair of cricketers (for a story about cricket) who arrived wearing normal clothes, and without a single cricket-related object between them. I once also photographed some computer wizards - who'd each (wrongly) assumed the other was bringing a laptop. And so on.

So, back to the two points of the article. One was that the job is much more than just taking pictures, because much of the time things aren't as we hope or expect. The second point touches on what to do with the 'curveballs'; with those trickier, unpredictable, desperate and even broken situations.

In gambling parlance - dealing with the latter is about knowing when to stick or twist. Or if you're religious, the beginning of the Serenity prayer sums it up:

"God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change; courage to change the things I can; and wisdom to know the difference."

But let's put it in terms of lemons.

Eating Lemons

Sometimes you can only do what you can do. You can't use lights, you can't influence proceedings, you can't change locations. You can't do anything other than take pictures. The important thing is to be aware of the limitations, and work out how you can mitigate their effect or work within them. Accept what there is and do the best you can with the choices which you are able to make (lens, position, composition). And convey this to the client without sounding like a whinger. So with the conference speaker who doesn't look up, it might be best just to go for a wide shot, including the surroundings. Then you're not making so important that he's looking down. I should just point out that there are a few near-certainties which save us in tough situations. You learn what these are with experience. Even someone at a lectern reading from a script will look up, even if only at the very end of their speech for a fraction of a second. It's all to do with the decisive moment, and knowing what's coming up.

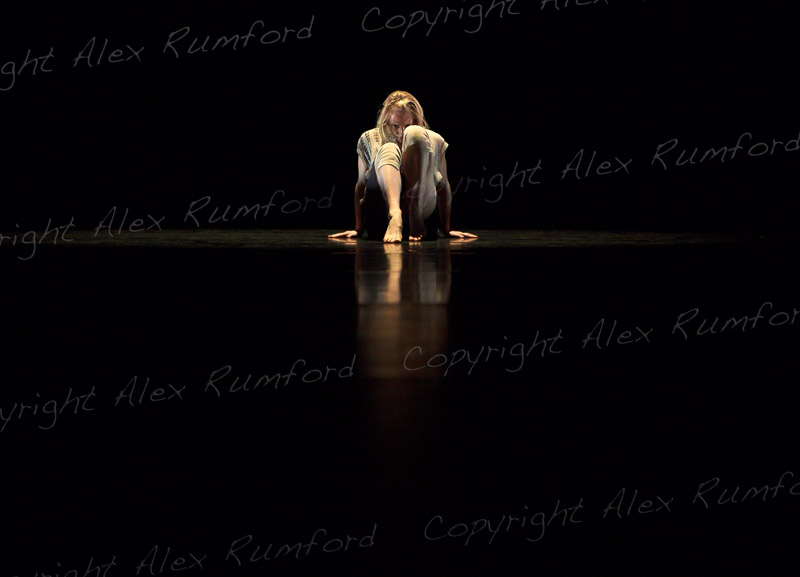

Anyway, another curveball: I remember photographing a (very) amateur dramatic youth production with poor lighting, everything spread out across the stage, no props or costumes to speak of, and no real action or interaction. Very little to do. The only thing left to do was to use a long lens and 'pick out' individual actors and their expressions and actions. The picture below is from a dance show, and is a similar example of something reasonable from out of not much, in this case through using a wider view:

Another example: I did some portraits of a trainee on a building site. I had a space (arbitrarily selected for me, without my input) of about three square metres to work within. Seriously. And there were no props***. Low angles, different lenses and a little changing of position still enabled us to get a reasonable variety of reasonable pictures, because at least the background was relevant. Here are a few from the shoot:

Making Lemonade

As pointed out in my other articles, many (most?) situations have a tendency to lead us thinking down logical paths. Certain kinds of shots present themselves, as other ones become unworkable.

When our preferred or expected shots are ruled out entirely, on occasion we can take those difficulties and turn them into opportunities. The job of the photographer is to know what's possible, to come up with a plan B on the fly. It's a remarkable way to focus the mind.

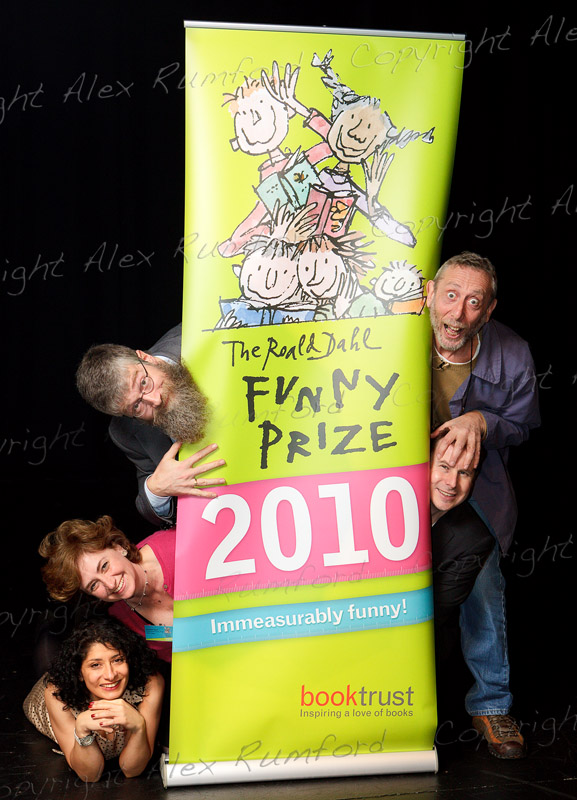

The example above comes from a situation where the banner needed to be in shot. Let's just say I'm not a big fan of banners, unwieldy as they are. Although, to be fair, this is probably the best one I've used. But then that's what I expect from the amazing Booktrust. By putting the banner centre, and having the people interact with it, it's not so much 'shoehorned in', as it is an integral element of the photograph. Imagine what the picture would be without the banner: a potentially dull group picture.

The example below had extremely hard sunlight causing problems. So we found a wall and turned the light to our advantage. It's a go-to shot which gets you out of a spot:

Swapping lemons for apples

With vision, it's sometimes possible to reject the situation entirely. This often applies to dire situations where we don't (appear to) have any input or control - and we then really push it. Part of this can be knowing when that is. It may be possible to interrupt, ask for something, go against what we're presented with, create something different - when we had previously been told (or had assumed) we couldn't do something or other, that we weren't permitted. This takes confidence. Of course, it may not be possible, in which case we're back to eating lemons...

A recent example was at an awards ceremony. I had been clearly instructed not to use lights for the performances between the speeches.

However, the lighting was awful. The background was awful. There were only a couple of (not very good) places for me to position myself. The performances - exciting as they were for an audience - would not work at all well (photographically) by themselves.

Well - I used my lights. And nobody stopped me. Nor was I reprimanded - it turned out that the client had just expected the lights to be much more of a nuisance than they were. They even said after that it had added to the sense of occasion. And the pictures were much better.

To be fair, this is quite an unusual example. More often is the situation where you have to use your position of expertise and overrule someone. To explain why something else entirely should be done, that's it worth the time or effort, that the current setup is no good. All the time, being aware that your client or subject may have strong feelings to the contrary, that someone might be at risk of losing face - and knowing that you have just one chance to prove yourself right. This is especially tricky where you are viewed as a 'snapper'.

So - to sum up: In these difficult circumstances the job is to know what is and isn't possible; what can and can't be changed; and to have the confidence to stick or to twist.

And what did I do with the picture with the bright afternoon sun which started this article off? I'd like to say I managed to rearrange everything quickly and smoothly, with clear vision and minimal fuss. Without offending anyone. But as it happened, a few small clouds had started to appear and pass overhead by the time we were to do this main photo. As there were several other shots to do, I got on with those first, quite happy to delay doing this main photo. I no doubt seemed to be stalling, but I simply wasn't confident we'd have a sufficiently large cloud for sufficiently long enough to cover us. I was, however, confident that the shot would be better than our other options - if we could get it. In other words, I didn't have a plan B and had nothing else up my sleeve.

And as it happened, we had a small window of opportunity, just enough time for about four frames with the sun behind a cloud, and I was happy enough with the shot, below. I suppose sometimes you just get lucky:

*What is ideal lighting? I suppose it depends what you're shooting. Remember that ideal can equate to safe - which can equate to boring.

**That may seem surprising - but in general I don't plan many types of shoots. I have a rough idea of what I might want to do, what the job might be, but so often it's more a starting point. Because as I keep saying, so many are different to what was promised or expected.

***While I think about it, if you haven't already, look at the articles I wrote on limitations.

****I appreciate the lemons analogy is starting to fail.

Seeing pictures

Back to basics

I think the most important thing to learn in photography is the most basic. It is the ability to see - to see things as they really are, or as they could be.

So often, we filter out the information before us. We see a pretty tree - but ignore the lamp-posts and ugly tower blocks surrounding it. We watch a raindrop running down a window pane - but block out the dull scene behind it. What we think we are seeing is really a distortion, often because we have decided what to see beforehand. A camera cannot distort the truth in this way. So we need to focus on what is really there. And, to me, it is one of the hardest skills.

What shape is a coffee cup?

We already have a distorted view of the world around us. We think of buildings as rectangular, the rims of coffee cups as circular, roads as straight lines. But if we actually look, we will see that a cup's rim is only circular when we are directly above it - not very often. All the rest of the time, it is an ellipse. To this day, I have never seen a rectangular building. They are usually experienced as trapeziums. And as we sit in a car, our own experience of viewing a road is not as a line, but almost always as a trapezium or triangle.

Our perspective changes our perceived shape of things - but we don't really take notice. Only when we look at a picture do we appreciate the difference between the geometry in our minds, and that which we experience (I must just add for anyone interested that the only shape that is always consistent, regardless of anything, is a sphere).

So much for shapes. Let's consider sunsets. I used to work for a newspaper, and readers would regularly send in pictures which they hoped would be published on the letters page. Often, these would be of fantastic sunsets, but all too frequently the photo would not do it justice. Lamp-posts, cars and trees would clutter the view. The clouds and setting sun would be dissected with telephone wires. The photographers had ignored what was in front of their eyes, in favour of seeing a pretty sunset. They had filtered out the rubbish. But no matter how interesting a subject, the 'rules' still have to be followed. And apart from these 'rules' of composition or framing, the first rule is that the camera can only show what is there, and is indifferent to what it sees.

It is hard to see the world as it really is. Often I am unable to visualise or imagine - see - what I'm actually looking at. No matter how much I squint, concentrate, mentally create a frame, I can't process the information. In these situations, I have to take a picture first, to see how it looks on the back of my camera. Only then do I get it. But this is for things right in front of me! What about seeing things that are so hidden, that - to most of us - aren't even there?

The art of seeing

Two masters in this art of seeing who spring to mind are Nils Jorgensen (www.nilsjorgensen.com) and Magnum photographer Martin Parr (www.martinparr.com). Good photography is frequently about showing the same things in a fresh way, and this requires really noticing and paying attention to what is around us. It involves real presence. Look at Nils' website and see how often you catch yourself nodding and saying, "Nice..." Go and buy some of Martin Parr's books. The greatest photographers (artists?) are not only seeing in photographic terms (shapes, lines etc.), but in terms of visual puns, cultural nuances, pointed comparisons of entirely unrelated things. It's awareness and presence on a whole new level.

Abstracts are a good example of a photographer seeing. They often involve taking an everyday object or scene, and emphasising an aspect to present it as something at first unreal or unrecognisable. It involves seeing with a further sense of imagination or exploration - a "what if?" - which gives us a fresh view. Silhouettes, close-ups, wayward cropping and composition are typically used to create abstractions.

Learning to see

Happily, there are tried and tested methods which photographers rely on. Similar kinds of pictures come up frequently which use the same ideas and techniques again and again - because they work. Look at newspapers, film posters, magazines, and you'll see a variety of interchangeable, overlapping and mixed elements which are combined to create images with impact.

I am convinced it is not always possible to get something really good from every situation, merely one can work to find the best that the situation offers. The real trick is knowing when a situation contains potential for something really good, and when it doesn't. Hence it is wise to have a few of these 'fallback' ideas to hand as a starting point. For most of us, the best way to learn is to borrow ideas from others. We then try out things for ourselves, and discover if we can 'see' something else.

I would finally add that often the most seemingly interesting thing simply will not work as a photograph, no matter what: there is nothing more to see. And other times the most apparently mundane situation can yield something extraordinary; there is real potential, if only we can find it. It is all about what works photographically. We need to be working always to see things in these artistic terms, then, and not through a filter of our own preconceptions.

-

June 2025

- Jun 19, 2025 The forever purge

- Jun 19, 2025 University prospectus

- Jun 11, 2025 Recent work - June 2025

- Jun 6, 2025 On Looking

-

January 2025

- Jan 21, 2025 The photographer's dictionary

-

November 2024

- Nov 19, 2024 Recent work - November 2024

-

September 2024

- Sep 17, 2024 Recent work - September 2024

-

July 2024

- Jul 4, 2024 Mean Girls

-

May 2024

- May 28, 2024 Wakehurst

- May 20, 2024 Graduation

-

April 2024

- Apr 16, 2024 Recent work - April 2024

-

January 2024

- Jan 22, 2024 Recent work - January 2024

- Jan 9, 2024 Long live the local

-

October 2023

- Oct 13, 2023 CBRE

- Oct 4, 2023 Recent work - October 2023

-

September 2023

- Sep 22, 2023 Seeing past the subject (2)

-

April 2023

- Apr 17, 2023 Tinder

- Apr 12, 2023 Recent work - April 2023

-

February 2023

- Feb 7, 2023 Will AI do me out of a job?

-

December 2022

- Dec 12, 2022 Freelance life and other animals

-

November 2022

- Nov 4, 2022 Recent work - November 2022

-

July 2022

- Jul 26, 2022 Recent work - July 2022

- Jul 25, 2022 SOAS

-

May 2022

- May 30, 2022 Ebay

- May 18, 2022 Physiotherapy

- May 4, 2022 Vertex

- May 4, 2022 Roche

-

January 2022

- Jan 6, 2022 Recent work - December 2021

- Jan 5, 2022 Prevayl

-

December 2021

- Dec 17, 2021 The day the hairdressers opened

-

December 2020

- Dec 15, 2020 SOAS - postgraduate prospectus

- Dec 7, 2020 Online teaching

-

October 2020

- Oct 11, 2020 Gratitudes

- Oct 5, 2020 GoFundMe Heroes

-

September 2020

- Sep 24, 2020 Headshots: why we need them, and why we don't like them

- Sep 15, 2020 From the archives - seven

- Sep 10, 2020 Recent work - September 2020

-

February 2020

- Feb 13, 2020 Mootral

-

November 2019

- Nov 7, 2019 Biteback 2030

-

October 2019

- Oct 2, 2019 Guinness World Records

-

September 2019

- Sep 16, 2019 B3 Living

-

July 2019

- Jul 22, 2019 Recent work - July 2019

- Jul 19, 2019 From the archives - six

-

April 2019

- Apr 15, 2019 Recent work - April 2019

-

March 2019

- Mar 12, 2019 International Women's Day

-

February 2019

- Feb 4, 2019 Recent work - February 2019

-

January 2019

- Jan 17, 2019 Four photographs

-

December 2018

- Dec 19, 2018 Handy gadgets and where to find them

- Dec 10, 2018 From the archives - five

-

November 2018

- Nov 26, 2018 How to compose photographs

- Nov 5, 2018 Recent work - November 2018

-

October 2018

- Oct 17, 2018 How to edit photographs in Instagram

- Oct 8, 2018 Out with the old

- Oct 4, 2018 Recent work - October 2018

- Oct 1, 2018 A little learning is a dangerous thing

-

September 2018

- Sep 12, 2018 From the archives - four

-

August 2018

- Aug 16, 2018 Recent work - August 2018

- Aug 15, 2018 I don't follow you

- Aug 6, 2018 Cookpad

-

June 2018

- Jun 7, 2018 Monks & Marbles

-

May 2018

- May 23, 2018 Netflix & Woof

- May 21, 2018 Best of Instagram

-

April 2018

- Apr 24, 2018 Standard Chartered Bank

-

March 2018

- Mar 16, 2018 Corporate self-portraiture (two)

- Mar 8, 2018 International Women's Day

-

February 2018

- Feb 9, 2018 Winter swimming

-

January 2018

- Jan 23, 2018 From the archives - three

- Jan 16, 2018 2017 in pictures

-

December 2017

- Dec 6, 2017 Toyota Mobility Foundation

-

November 2017

- Nov 24, 2017 Corporate work

-

October 2017

- Oct 31, 2017 Recent work - October 2017

- Oct 13, 2017 Pfizer - Protecting our Heroes

-

September 2017

- Sep 21, 2017 Campaign portraits

-

August 2017

- Aug 22, 2017 Wyborowa vodka

- Aug 1, 2017 Vauxhall animation

-

July 2017

- Jul 31, 2017 Tanguera

- Jul 20, 2017 Take your parents to work

-

June 2017

- Jun 22, 2017 Recent work - June 2017

-

May 2017

- May 22, 2017 Mannequins (female)

- May 16, 2017 Scott Reid

- May 9, 2017 Huawei - The New Aesthetic

-

April 2017

- Apr 24, 2017 S.H.O.K.K.

- Apr 21, 2017 Battle

- Apr 18, 2017 Ashburton

- Apr 11, 2017 Victoria Jeffrey

-

March 2017

- Mar 30, 2017 Parkour Generations

- Mar 27, 2017 War Horse in Brighton

- Mar 23, 2017 Rock'n'roll

- Mar 20, 2017 Jane Eyre

- Mar 15, 2017 Patricia Cumper

- Mar 8, 2017 1000 Pieces Puzzle

-

January 2017

- Jan 23, 2017 Framing 101

- Jan 10, 2017 View from the gods

-

December 2016

- Dec 14, 2016 Studio Fractal

-

November 2016

- Nov 29, 2016 Musician

- Nov 21, 2016 Gavin Turk

- Nov 10, 2016 While I was waiting...

- Nov 3, 2016 Canvas

-

October 2016

- Oct 28, 2016 Rishi Khosla

- Oct 18, 2016 Sadlers Wells workshop

- Oct 11, 2016 Rose Bruford

- Oct 6, 2016 Making lemonade at Harrods

-

September 2016

- Sep 28, 2016 Money Mentors

- Sep 21, 2016 Instawalks

- Sep 12, 2016 Mannequins (m)

-

August 2016

- Aug 23, 2016 Tomorrow's People

- Aug 17, 2016 Mousetrap

-

July 2016

- Jul 28, 2016 Property brochure

- Jul 19, 2016 Choosing between photos

- Jul 8, 2016 Create Victoria

- Jul 1, 2016 Recent work - July 2016

-

June 2016

- Jun 21, 2016 Cohn & Wolfe 2

- Jun 10, 2016 Physical Justice

-

May 2016

- May 31, 2016 Corporate self-portraiture

- May 23, 2016 Photivation (two) & Instagram

- May 16, 2016 From the archives - two

- May 4, 2016 Red Channel

-

April 2016

- Apr 28, 2016 GBG corporate shoot

- Apr 21, 2016 28 days later

- Apr 14, 2016 Colgate

- Apr 6, 2016 Breaks and burns

-

March 2016

- Mar 31, 2016 Mixed bag

- Mar 22, 2016 Pearson

- Mar 15, 2016 War Horse - The Final Farewell

- Mar 8, 2016 The Jersey Boys

- Mar 1, 2016 Sky Garden

-

February 2016

- Feb 23, 2016 Avada Kedavra!

- Feb 17, 2016 Bees

- Feb 8, 2016 From the archives

-

January 2016

- Jan 27, 2016 Kaspersky - Alex Moiseev

- Jan 19, 2016 Melanie Stephenson

- Jan 11, 2016 Photivation

-

December 2015

- Dec 28, 2015 Noma Dumezweni

- Dec 17, 2015 Creating a portfolio

- Dec 8, 2015 Victoria

- Dec 1, 2015 Collabo

-

November 2015

- Nov 25, 2015 Danny Sapani

- Nov 17, 2015 People, Places and Things

- Nov 10, 2015 Romain Grosjean

- Nov 2, 2015 Egosurfing

-

October 2015

- Oct 23, 2015 The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time

- Oct 13, 2015 This Girl Can

- Oct 1, 2015 Ratings are overrated

-

September 2015

- Sep 23, 2015 Indra

- Sep 15, 2015 Seeing past the subject

- Sep 8, 2015 Black and white (two)

- Sep 2, 2015 The decisive moment (two)

-

August 2015

- Aug 25, 2015 British Gas

- Aug 19, 2015 Problem solving vs creativity

- Aug 12, 2015 Cohn & Wolfe

- Aug 5, 2015 James

-

July 2015

- Jul 31, 2015 Photographing the photographer

- Jul 28, 2015 Black and white

- Jul 20, 2015 Comedian

-

December 2014

- Dec 15, 2014 2014 in pictures

-

January 2014

- Jan 9, 2014 2013 in pictures

-

February 2013

- Feb 10, 2013 It's not the camera

-

December 2012

- Dec 31, 2012 2012 in pictures

-

April 2012

- Apr 30, 2012 What the job is - or, "Dealing with lemons"

- Apr 13, 2012 Your holiday photos aren't rubbish

-

May 2011

- May 13, 2011 Showing the world differently

- November 2010

-

October 2010

- Oct 9, 2010 Seeing pictures