A little learning is a dangerous thing

“Do you still improve as a photographer?” a friend asked recently. What an odd question - I’ve been doing it for nearly 15 years, and have only in the last few reached a point where I’m not constantly worrying and feeling like a fraud. All I ever strive for is improvement. It’s a strange idea that one day you just ‘get it’ and you’re done.

I realised three things.

One is that you don’t ‘just get’ anything. Everything can be improved. Even walking? Yes, I’m pretty good at that, but put me on a catwalk and I’d like some lessons first. What about drinking? Maybe, but ask the people who taste coffee, buy wines, and you’ll find there’s more to it.

Two is that any assumption - here, that photography is something you ‘get’ - is based, in part at least, on our being unable to see, judge or understand anything much outside our sphere of knowledge. On a recent weekend in Dublin, my Irish hosts were stunned I couldn’t hear the difference between their accents - Galway, Cork, Derry*. Why would I? But while not important to me, it is where it concerns one’s identity within a country. Or to take another example: I’ve barely touched my guitar in 20 years (and was only Oasis-round-the-campfire level then). Yet my kids think I’m a rock legend. Because they don’t know better, I’m up there with Slash and Jimmy Page. Who they don’t know.

Three is that improvements must become smaller. What I learn in the next few years will be far less than what I learned in my first years as a freelance. Or to put it another way, I need to work much harder now to to improve the same amount**.

Anyway, the following diagram - which I came across some years ago - describes the learning process from beginner to expert, and applies to any skill or ability - driving a car, playing the piano or, indeed, practising photography.

Stage one is 'unconscious incompetence'. This is where you have a subject which you don't know about, and, moreover, you don't know what you don't know. This could be something like the stock market, interior design, or Bolivian basket-weaving. It applies to most things, for most people.

The next stage is 'conscious incompetence'. You have a basic grasp of a subject, and realise there’s a lot more to learn. This applies to the well-read, the busy, the educated and the hobbyists, about most things.

The third stage is 'conscious competence'. You are practised enough to do it, aware of how far you've come, and aware of what else there is to know and learn. The most basic techniques are perhaps second-nature, but the bulk of performing the activity is very much a conscious process.

Then, at stage four, we reach 'unconscious competence'. The knowledge acquired is now hardwired in the unconscious part of the brain through practice and/or study. Almost as if you're not aware of what you know - it's second-nature. Like riding a bike. Or, like speaking in our native tongue, we can produce and process complex sentences at will, taking into account grammar, vocabulary, intonation and body language. But most of us would be unable to analyse or explain the compound verbs, adjuncts, facial clues or speech patterns we use so readily.

There’s also "reflective competence", which is to do with a self-awareness and deep understanding of a subject, the kind required for teaching or writing. It might also suggest an ability to adapt and respond naturally to entirely new challenges.

Or, the arrow could lead back to stage one. Unconscious competence can lead to complacency and habit as one develops a personal style, set along certain ways of doing things, and self-belief becomes stronger. It can be hard to learn (or one might actively resist) new techniques or accept new ideas, and to do so requires starting again, at least in some way. I remember as a student the feeling of ‘unlearning’ what style I’d had as a keen amateur.

Competence and the Critical Eye

Bringing it back to photography, as you improve and get the basics under your belt, you being to notice things previously hidden or ignored. Things which didn't bother you before - didn't even appear on your radar - now become issues to deal with. Your pictures get better through experience, but as this learning finds its way into your work, you become more critical of them. In learning what to 'look for', so you see those things when you judge the picture later. Messy backgrounds, dead space, and burnt-out highlights never bothered me when I started out. They simply didn't register. But looking now, these flaws would be the first thing I see and all I notice. Hopefully, in the years to come I'll feel the same way about the pictures I have in my portfolio now. Because if not, I'm not improving.

For me, this is where doing photography and viewing photography overlap. Doing photography takes place in real time, with all the difficulties and problems that brings. The better you become, the 'higher' the concerns which you need to consciously think about, concerns which didn’t exist before. And with these newer concerns on your mind, when you view the pictures later, these are the things you may (or may not) have got right. Those are the new benchmarks by which you judge the success of the shoot.

Ars est celare artem

And the higher up you go, the more theoretical they become. For the really good photographers, the 'rules' count for less and less. Some of the greatest pictures can look, at first glance, almost like amateur snapshots, in my opinion. They look easy, without any apparent art or style. The Latin quotation above (sometimes incorrectly attributed to Ovid) loosely translates as "Art is the concealment of art", or "Art hides itself". The idea is that the greatest art lacks overt ingenuity or self-conscious craftsmanship. It doesn't seem to present itself as art - until you look closer. It suggests that you need to be at a certain 'level' to really appreciate it. And one recognises that improvements are harder and harder to get: the final few metres are what separates the good from the great.

The Dunning-Kruger effect

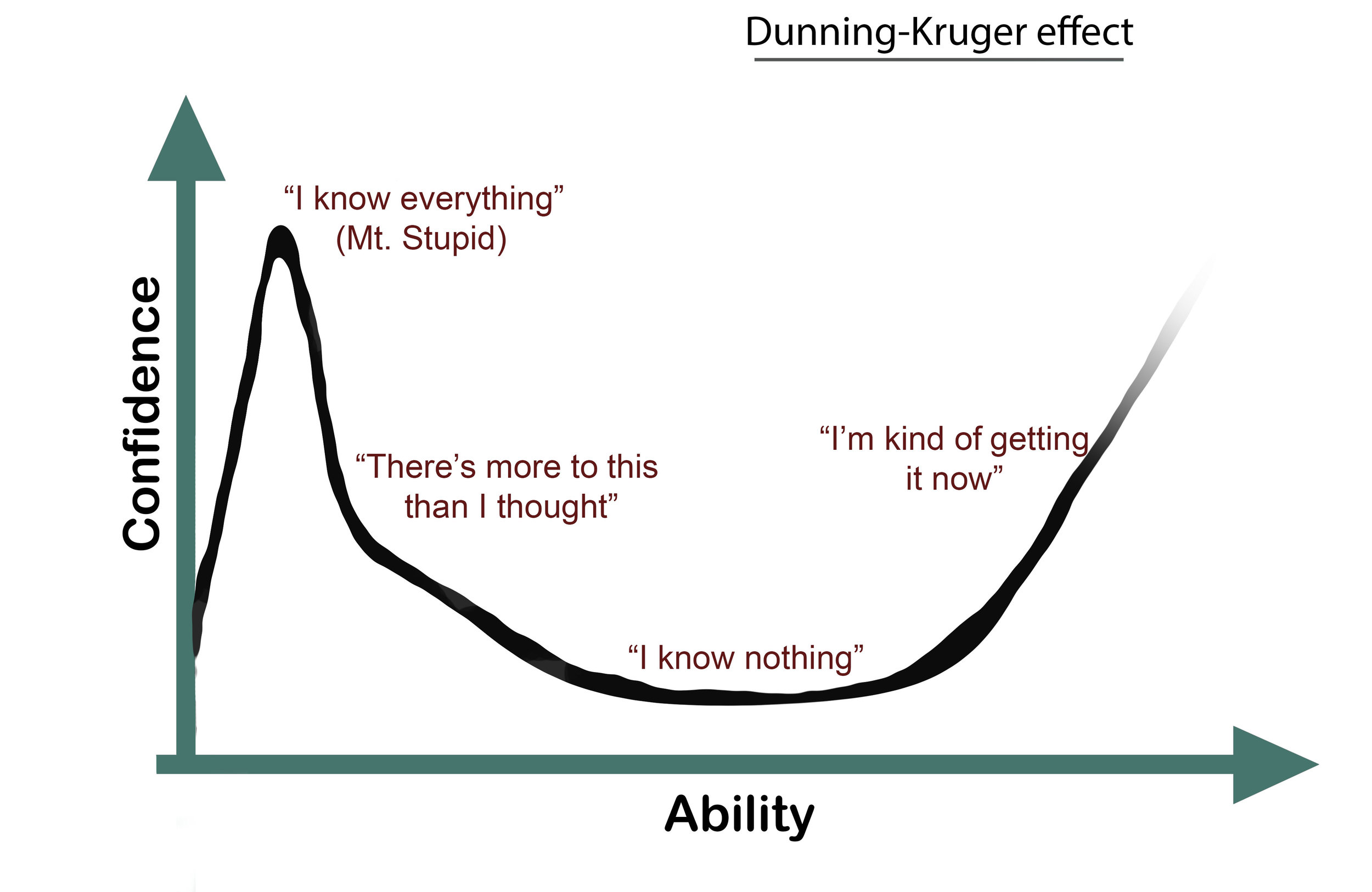

Going back to the second idea (how little we really know, when we know very little), this is a symptom of unconscious incompetence. The model below describes the relationship between one’s ability and one’s confidence:

After only a short time learning a new skill, we feel we know a great deal. Probably because even after a few lessons (in anything), we’re already ahead of 98% of people. But soon enough, our self-belief plummets (consciously incompetent), before we begin to build up our ability and confidence at a more equal ratio (consciously competent).

Alexander Pope described the behaviour in 1709:

“A little learning is a dangerous thing;

drink deep, or taste not the Pierian spring:

there shallow draughts intoxicate the brain,

and drinking largely sobers us again.”

I’d like to think “I’m kind of getting it now” with regards photography. And I’d point out that if we knew from the start how much there is to learn about something, we’d probably never bother to do anything. A little ignorance and a touch of unwarranted confidence is a helpful nudge to get things started.

*If I’m honest, I sometimes struggle hearing between Scottish and Irish.

**An analogy from Breaking Bad: Gale Boetticher’s meth reaches 96% purity, yet he is in awe of Walter’s 99.1%.