Seeing pictures

Photography 101

The most important thing to learn in photography is the most basic: how to see things as they really are.

This might sound like a rather meaningless admonishment, a Zen-flavoured version of “pay better attention”. But while that is part of it, that’s not what I’m talking about.

I’m talking about how we constantly filter the world. And while this is a normal process - and indeed essential most of the time - we go about out lives unaware we’re doing it. And, when taking pictures, it works against us.

If you didn’t click the link, I’ll summarise how it relates: we’ll notice the beautiful tree in the sunlight, but not the disused phone box and the lamp post cluttering the background. Or, while watching melancholy rain run down our window, we’ll somehow ignore the dull scene behind it, which contains an Amazon delivery van and some wheelie bins. And that winter sunset scene from our patio is one thing as an experience, but we disregard the contrails, the telephone wires and the buildings which obscure it.

A camera doesn’t do this. It records everything, exactly as is.

And this is why we might complain that a picture didn’t come out well, or that it didn’t do something justice. There’s a disconnect between what we notice and what’s actually there. We felt something, but the camera failed to capture it.

So, just because something looks good to our eyes in the moment - enough to move us into taking a picture - it does not mean it’s going to work photographically. In short, what you’re looking at is often only the most salient part. It’s the most attractive, interesting or photogenic aspect of what’s right in front of you. Everything else - those busy, untidy, boring details which comprise most of the scene - you’re filtering out.

Why things look different in photographs

Our minds simplify in order to process reality. There’s just far too much information, and we filter for what we’re paying attention to.

But to be clear, I’m not (just) referring to messy backgrounds we fail to register.

There’s another part to this, a second thing we do, harder to define and which is - arguably - more problematic.

We create mental models to help us navigate the world, and the issue (at least for photography) is that they’re often inaccurate.

Let’s use shape as an example:

What shape is the rim of a coffee cup?

What shape is a road?

What shape is a building?

If you said circle, rectangle and line then you scored 0. In the abstract, and day-to-day, sure, they’ll do as answers. But this is not how we experience them in unfiltered reality: and it’s therefore not how the camera sees them. Let me clarify:

A cup’s rim is an ellipse in our experience. It’s a circle only when viewed from above (which is almost never).

Not a rectangle. The Brutalist Archway Tower, North London, is a (wonky) trapezium as seen from the ground. Note that if it were higher it would approximate a triangle.

2. Buildings are trapeziums in our experience (or, from the side - if you’re interested - irregular quadrilaterals). They only ever approximate rectangles when you’re viewing them from far away (rarely in a city). If you don’t believe me, scroll through your phone and try to find a photo containing a building which is a rectangle (four straight sides; four 90° angles; parallel opposite sides which are equal in length).

Not a straight line. This road, somewhere in the middle of America, is a triangle as experienced from a driver’s point of view.

3. Roads are triangles. They’re straight lines on maps, yes, because a birds-eye view is the most useful model, but - again - in our experience they’re triangular. Stand in the middle of any road at look towards the horizon and you’ll see. Or look up images of “Route 66” and compare the maps and the photos for a direct comparison.

And yet, even though we know that perspective changes geometry, we keep getting returned to our simple geometric model of the world, because most of the time that’s a more useful OS. (Fun fact: a sphere is the only shape that always looks the same.)

The camera and the eye

There’s another part to these disconnects which deserves an aside. It’s to do with the difference between the camera and the eye; and even what a photograph is. It’s so fundamental that we don’t even think about it. But it’s not a failing on our part. It’s simply a set of considerations to keep in mind, and perhaps exploit. I’ll briefly note some of them:

Most obviously, we exist in time, whereas a photo is only a moment. You’ll never see a bullet being fired, nor a silky waterfall, nor star trails. So whether the camera shutter is open for a fraction of a second, a minute, or several hours, it only approximates reality.

Along the same lines: a photograph might be a 12x8 print. Its composition, chosen. Its crop - what it includes and leaves out - deliberate. Its physical frame and even its placement on a wall selected carefully, where factors of cost and lighting come into play. Anyway, this piece of art, eternalised behind glass, has nothing to do with our day to day experience.

There’s the field of vision: our eye approximates a 50mm lens. So anything else - wide-angle, macro, tilt-shift, or telephoto - is bending light and while often this difference is one we barely register (oddly), at the extremes we recognise a world we’re not privy to: the very small, or the very large / far away. In the case of the James Webb Space Telescope we are, in a very real sense, looking back in time!

Dynamic range: our brains and eyes are adapted to see dark and light across the same scene pretty well. A camera is far more limited here. One result of this is higher contrast, and one result of this is the silhouette, which just aren’t anywhere as common as photographer’s portfolios would have you believe.

Colour perception: our clever brains “correct” based on (assumed) ambient light, so that we might see something as white and gold, whereas it’s actually blue and black. Or the other way around. I don’t know. More than this, our feelings are weighted and influenced by colour, so, for instance, we think of orange as warm and blue as cold. From branding and advertising, to signage, storytelling and art we exploit colour theory relentlessly, but there’s nothing inherently “creative” about green, or “traditional” about brown, say. They’re just wavelengths.

What the hell do we do about all this? How does this knowledge help us learn and improve? How can we learn to see better? Why not just go back to bed?

Bed is a great option here, but here are a few tips to improve your photos on the back of all this:

Simplify. If you can honestly describe the image in a few words, you’re on the right track. Is the caption “Sunset over the trees”? Or is it, more accurately, something like “Sunset over the trees, two lamp-posts, a tower block, some birds and the tops of some people’s heads”? The former description, the simpler one, refers to a more impactful image. There are ways to simplify (to be covered in more depth in an upcoming article on how to improve your photography), but very often we can simplify by getting closer (usually the better option), or zoom in. The closer we go, the more we remove the bins and lampposts at the edges of the frame, and indeed anything-not-the-subject. Moreover, it makes our subject larger and more prominent.

Take lots of photos. Try different heights, changing viewpoints; from different places and with different compositions. From further back and closer in. Then look through them later: compare and contrast. You can’t notice everything in the moment, but you can at your leisure, and having a range of options to go through will yield some which are better than others. Better, meaning simpler, or easier to read*.

Wait. For literally anything where there’s potential movement or change, try to predict what might happen and wait. Situations change and develop, and there are certain moments where things just look ‘better’ for a photo. Like the previous suggestion, with a few different moments captured, and reviewing them at our convenience, we begin to be able to notice details when comparing shots frame by frame. We learn to be sensitive to the differences even a small amount of time can make to a scene, a mood, or a situation.

Follow the rules. As I’ve been emphasising, no matter how impressive the subject, an image still benefits from applying the ‘rules’ of art. This range of (easy-to-learn!) photography techniques are tried and tested. There are ten rules / go-to methods, and I use them relentlessly.

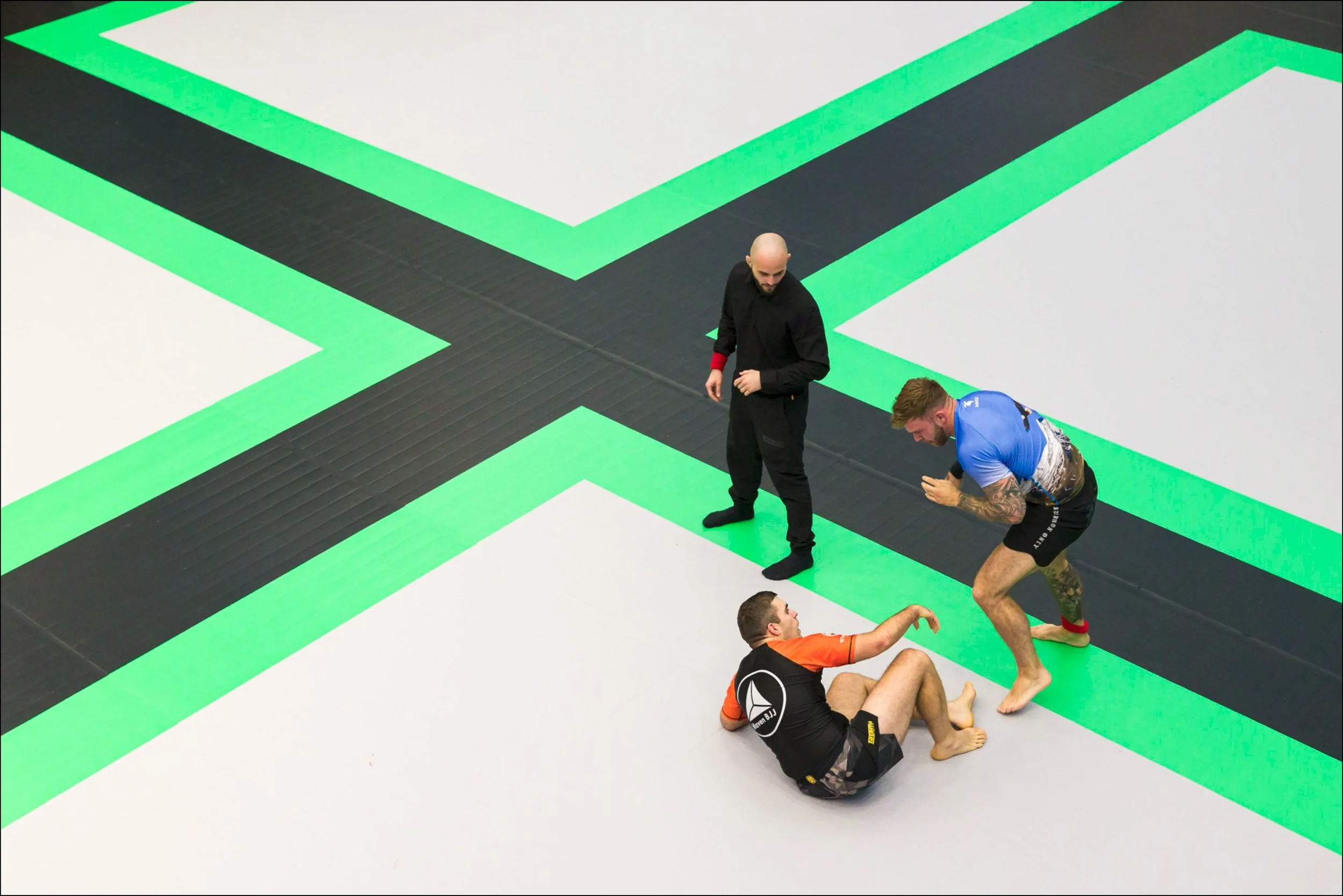

This shot of a jiu-jitsu match relies on Rule 4 (“the look-down”) and the much-hated Rule ⅓ (the rule of thirds). It also uses diagonals and colour.

And this photo (someone examining the fabric on a kimono) uses exactly the same ideas.

5. Recompose. Composition is the only thing we have control over in the moment, but - alas! - our intuitions are lazy: we’re inclined to put the subject in the centre, because that’s how we look at things. But, as with the earlier comment about the 12x8 print, we’re often not showing the world as it is - that’s boring and predictable - we’re going further and creating something in the viewfinder which works as a photo. So once you’ve taken the shot with your subject in the centre, try it to the right, on the edge etc. and analyse the difference this makes. Try to notice why some work, and some don’t.

6. Try abstract photography. This genre in particular takes head on our difficulty in seeing things as they are. It’s seeing past flowers / people / sunsets / cats as the subject; and taking the shapes, lines, textures, details and colours which compose them as the subject. It’s very accessible: anything is fair game, and it’s all personal taste. The shadow of your coffee mug in the morning. The wrinkles on your hand. The red of a sign.

One more thing you can do anywhere to learn to see better

Next time you’re on a train, going for a walk, or even just sitting on the sofa, pick a visual theme. It doesn’t matter what. The colour green. Flat objects. Ellipses (circles, if you must). Things in shadow. Diagonal lines. Reflections. Don’t take any photos: just try to notice them where you see them.

Ultimately, photography isn’t about photographing “interesting things” - that’s subjective - it’s about noticing what works visually, and what doesn’t. And by practising, we can then take our interesting things and elevate them into good photos.

*We do talk about ‘reading images’ - so perhaps it’s helpful to think of a photo as a short story, haiku, or a one-liner.